- Regular Expressions Learning Objectives

- HTTP Full-Stack Learning Objectives

- The Uniform Resource Locator (URL)

- Regular Expressions Cheat Sheet

- RegexOne Practice

- HTTP

Full-Stack Project

- Project overview

- Get started

- Phase 1: Installing one tool

- Phase 2: Getting the server started

- Phase 3: Understand the code

- Phase 4: Showing images

- Phase 4b: No image found

- Phase 5: Showing a static HTML page

- Phase 6: First step in dynamic content

- Phase 7: Handling the adding of an item

- Phase 8: Generate dynamic content

- Phase 9

- Complete!

- <=(Express)==>

- Express Learning Objectives

- Pug Template Learning Objectives

- Moving Into the Express Lane

- Templating - Meet Pug!

- Digging Into the Pug Template Syntax

- Exploring Route Paths

- Express Routers

- Routing Roundup Project

- <=(Form Handeling)==>

- HTML Forms Learning Objectives

- HTML Forms: An Introduction

- HTML Forms in Express

- Data Validation

- Express Middleware

- Protecting forms from CSRF

- Formative Forms Project

- <=(Data Driven Ap)==>

- Data-Driven Web Sites Learning Objectives

- Acclimating to Environment Variables

- Asynchronous Route Handlers in Express

- Handling Errors in Express

- Data-Driven Websites - Part 1: Setting Up the Project

- Data-Driven Websites Project (Part 2: Integrating Sequelize with Express)

- Data-Driven Websites Project (Part 3: Using Sequelize to Perform CRUD Operations)

<=(Node HTTP Servers)=>

- <=()>

- Regular Expressions Learning Objectives

- HTTP Full-Stack Learning Objectives

- The Uniform Resource Locator (URL)

- Regular Expressions Cheat Sheet

- RegexOne Practice

- HTTP

Full-Stack Project

- Project overview

- Get started

- Phase 1: Installing one tool

- Phase 2: Getting the server started

- Phase 3: Understand the code

- Phase 4: Showing images

- Phase 4b: No image found

- Phase 5: Showing a static HTML page

- Phase 6: First step in dynamic content

- Phase 7: Handling the adding of an item

- Phase 8: Generate dynamic content

- Phase 9

- Complete!

- <=()>

Regular Expressions Learning Objectives

Regular expressions are a delight and a nightmare. They please and they

confound. They are an important part of every developer's toolbox. By the time

you finish this, you should be able to

- Define the effect of the * operator and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the ? operator and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the + operator and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the . operator and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the ^ operator and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the $ operator and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the [] bracket expression and use it in a regular

expression - Define the effect of the - inside brackets and use it in a regular expression

- Define the effect of the ^ inside brackets and use it in a regular expression

HTTP Full-Stack Learning Objectives

Understanding how Node.js handles incoming HTTP requests using the

IncomingMessage and ServerResponse objects provide a strong foundation of

being able to predict problems when you use frameworks to ease the burden of

writing Web applications. When you complete the associated material for this

lesson, you should be able to:

- Identify the five parts of a URL

- Identify at least three protocols handled by the browser

- Use an

IncomingMessageobject to- access the headers sent by a client (like a Web browser) as part of the HTTP

request - access the HTTP method of the request

- access the path of the request

- access and read the stream of content for requests that have a body

- access the headers sent by a client (like a Web browser) as part of the HTTP

- Use a

ServerResponseobject to- write the status code, message, and headers for an HTTP response

- write the content of the body of the response

- properly end the response to indicate to the client (like a Web browser)

that all content has been written

The Uniform Resource Locator (URL)

We use URLs all the time. Now, it's time to really understand how they work.

From this reading, you should be able to

- Recall where to find the definition of a URL,

- Identify and recall the five components of a URL, and

- Identify properly formatted URLs

The specification

Almost all good things that define how the Internet works has one or more things

called IETF RFCs which define how they work. There are two acronyms there:

- IETF: Internet Engineering Task Force

- RFC: Request For Comments

The IETF is an open standards organization that creates voluntary standards to

maintain and improve the usability and interoperability of the Internet. Things

like the way travels across the Internet is created an maintained by the IETF.

In particular, the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol is now governed by RFC

5321. RFC 5321 made obsolete RFC 2821 which, in turn, made obsolete RFC 821.

The IETF is always working to make the Internet better with respect to its

growth and usage.

An RFC is a document usually created by programmers, engineers, and scientists

in the form of a memorandum. They publish the RFC for peer review. When enough

people have reviewed it, and it seems worthy of adoption, the IETF will change

its status to "Internet Standard" which means that everyone should comply with

it if they implement that standard.

The RFC 3986, Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic

Syntax, is an

"Internet Standard". That means that software applications that use URLs need to

conform to the specification found in that document lest they be publicly shamed

by computer programmers trying to use the non-conforming software.

What is this "resource" thing?

Well, the standard doesn't do much for you in providing a definition of this

word "resource".

This specification does not limit the scope of what might be a resource;

rather, the term "resource" is used in a general sense for whatever might be

identified by a URI. Familiar examples include an electronic document, an

image, a source of information with a consistent purpose (e.g., "today's

weather report for Los Angeles"), a service (e.g., an HTTP-to-SMS gateway),

and a collection of other resources. A resource is not necessarily accessible

via the Internet; e.g., human beings, corporations, and bound books in a

library can also be resources. Likewise, abstract concepts can be resources,

such as the operators and operands of a mathematical equation, the types of a

relationship (e.g., "parent" or "employee"), or numeric values (e.g., zero,

one, and infinity).

That influence comes from one of the authors, Dr. Roy Fielding. He has some

strong ideas about how the Internet works and, much to his disappointment, it

continues to move away from his ideals.

For your purposes, a URL points to a (hopefully) accessible resource that can

be accessed, like HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and pure data in the form of JSON.

The components of a URL

In Section 3, Syntax Components, of RFC 3986 contains this helpful ASCII art

graphic to show you the components of a URL.

foo://example.com:8042/over/there?name=ferret#nose

\_/ \______________/\_________/ \_________/ \__/

| | | | |

scheme authority path query fragment

Here's an explanation of each of those components.

The "scheme" of a URL

This section used to be called "the protocol", but was updated when URLs became

part of a larger family known as URIs, Uniform Resource Identifiers, which is

what RFC 3986 actually covers.

You've actually used three schemes already in class! Can you remember them?

If you replied "http" and "https", that's right! When you type an authority in

the browser, like "duckduckgo.com" or "localhost:3000", the browser

assumes that

you want to use HTTP, so it prepends that scheme to the authority. The browser

would then make requests to "http://duckduckgo.com" or "http://localhost:3000".

When you double click on an HTML file and it opens locally in your browser, that

is using the "file" scheme, meaning that it is looking for a file local to the

computer! You've done this countless times during this course. You may have

noticed the "file" part in the address bar. That's the scheme it used to access

local files as opposed to making an HTTP request.

This is why it was once named "protocol", because it was the protocol that the

browser would use to locate the resource using a Uniform Resource Locator.

Stuff between the scheme and authority

The standard tells us that for URLs that have an authority, the characters "😕/"

must exist between the scheme and the authority. That's why you have to type

those characters. You can blame Sir Tim Berners-Lee for that because he defined

it in the original RFC for this subject, RFC 1738, Uniform Resource Locators

(URL).

The authority

This part of as URL is normally the domain name of the resource that has the

resource that you're trying to access.

Sometimes it has a port number, too, like when you start a local HTTP server

with Node.js. Then, you type "http://localhost:3000". The authority is

the

entire "localhost:3000". That means that, even if "http://localhost:3000"

and

"http://localhost:8081" return the exact same content, they're considered to

be

two different URLs to the same content.

The path

Paths are in the first part of an HTTP request, if you recall. When you click on

a link in your browser that takes you to "https://duckduckgo.com/about", that

results in an HTTP request that begins with the following line:

GET /about HTTP/1.1

That's the path.

If the path is omitted from a URL, it is assumed to be "/".

The query

This is extra information sent to the browser meant for the processing of the

request. For example, when you go to DuckDuckGo and perform a search for "RFC

3986" by typing it into the search box, the URL that your browser is directed to

reads "https://duckduckgo.com/?q=RFC+3986".

The question mark and everything that comes after it (up to the fragment) is

considered the "query" of the URL. Because it's part of the URL, it means that

different values of the query part of the URL points to different resources even

if the exact same content is returned.

With respect to URLs used for the World Wide Web, queries generated by browsers

(and possibly by your code) will have the following format:

- Entries in the query are "URL encoded" key-value pairs with an equal sign

between them - Entries are concatenated with the ampersand symbol

When the key or value of an entry in a query contains a character that is not

one of the reserved or unreserved characters, then it gets "URL encoded". That

process replaces each character a percent sign and its hexadecimal ASCII Code.

For example, when your provide the value "Mary" and "/" because those

aren't allowable characters. Those characters' ASCII Code values are 24 and 2F,

respectively. That transforms the string to "Mary%24quite%2Fcontrary".

Luckily, JavaScript has built-in methods called encodeURI (link) and

decodeURI (link) that

handles that transformation for you!

The fragment

The fragment is never sent to the server. Instead, it tells the browser to

access a specific section of the page after it loads. For example, if you look

at the following link

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/URL#Protocol-relative_URLs

you can see that there is a fragment value of "#Protocol-relative_URLs". If you

click on that link, the browser will load that page and, then, scroll that

section into view for you.

Unlike with changing values in any of the other sections, if you change the

value in the fragment, the browser will not reload the page.

Reading RFCs

Unfortunately, RFCs tend to be very unappealing and technical, not fun to read

at all. However, you should try reading them when you have a question about how

something works that's governed by the IETF. You will gain insight that only

comes from technical documentation.

As a side note, it is a common thing for programmers to publish April Fool's

RFCs. Their sense of humor is ... shockingly technical and dry. Here are some

interesting ones, for example.

- Hypertext Jeopardy Protocol (HTJP/1.0)

- Design Considerations for Faster-Than-Light (FTL) Communication

- TCP Option to Denote Packet Mood

Yep, that's the kind of humor in deeply computer science-y groups.

¯\(◉◡◔)/¯

What you've learned

You learned that the five parts of a URL are

- The scheme (required),

- The authority (required),

- The path (optional),

- The query (optional), and

- The fragment (optional, not sent to the server).

You were reminded that you actually know three schemes: http, https, and file.

And, that's it for URLs. 😃

Regular Expressions Cheat Sheet

This article lists the most commonly-used regular expressions operators. You

can use it as a handy reference for later while you write regular expressions.

The * operator

The * operator is known as the Kleene Star, one of the Kleene operators.

You use the Kleene Star operator to match any number, zero or more, of the

character it follows.

For example, take the following regular expression patterns and compare them

with the strings below:

Example 1: xy*z

Matches:

xxz

xyyyzzz

Does not match:

yyy

xyxz

Example 2: x*yz

Matches:

xxyz

yyyzzz

Does not match:

xxx

xyyz

Example 3: xyz*

Matches:

xy

xxyzzz

Does not match:

zzz

xyyz

The ? operator

The question mark operator denotes that the character preceding ? is an

optional character. Note that when you want to use a

normal question mark as a

normal character and NOT as a regular expression operator, you need to escape

the character with a forward slash like \?.

Take the following pattern and compare it with the strings below. Notice how

the s? portion of the expression makes the "s" character optional, allowing

the pattern to match both "video" and "videos".

Example 1: videos?

Matches:

cat video

dog videos

Does not match:

bird vids

hedgehog vides

Example 2: videos\?

Matches:

dog videos?

videos? hello?

Does not match:

cat video

videos

Note different effect of the regular expression with an escaped question mark

verses a non-escaped question mark.

Example 3: videos? watched\?

Matches:

dog video watched?

cat videos watched?

Does not match:

bird video watched

hedgehog videos not watched

The + operator

The + operator is known as the Kleene Star Plus. You use Kleene Star Plus

to match one or more of the character it follows, instead of zero or more

like the Kleene Star.

For example, take the following regular expression patterns and strings below:

Example 1: xy+z

Matches:

xyyyzzz

xxxyzz

Does not match:

xxz

xyxz

Note how "xxz" is matched by xy*z but not by xy+z.

Example 2: x+yz

Matches:

xyzzz

xxxyzz

Does not match:

yzz

xyyz

Example 3: xyz+

Matches:

xyzzz

xxyz

Does not match:

xy

xxy

The . operator

The dot operator matches any single character. It acts as a wildcard that

can match any single number, letter, symbol, or even whitespace. Like the

question mark operator, in order to use . as a normal character instead of a

regular expression operator, you need to escape the character with a forward

slash (\.).

Take the example expressions and strings below:

Example 1: ..a..

Matches:

12aa3

brains

Does not match:

123a4

catch

Example 2: .at.

Matches:

?att

catch

Does not match:

1a1t

atss

Remember that using a forward slash before a question mark in a regular

expression escapes the question mark so that ? is not interpreted as a

regular expression operator.

Example 3: ...\?

Matches:

123?

????

Does not match:

123

?cat

The ^ operator without brackets

The ^ operator is known as the hat operator. The hat operator can be used in

two ways:

- Without square brackets to match the start of a line.

- Within square brackets to denote when you want to exclude characters.

When using ^ at the beginning of a regular expression pattern, you are

indicating a match with statements that begin with the characters in your

pattern. Note the case sensitivity in the examples below.

Example 1: ^Dog

Matches:

Doggie daycare

Dog food

Does not match:

doG master

puppy Dog

Example 2: ^dog

Matches:

doggie

dogs

Does not match:

hotdog

small dog

Example 3: ^\?

Matches:

? hello

???

Does not match:

hi?

\?bye

The $ operator

The dollar sign operator is used to define the end of a line. Like how the ^

hat operator is used to specifically match the beginning characters of a line,

the $ dollar sign operator is used to specifically match the end of a line.

Take the following patterns and strings below:

Example 1: smell$

Matches:

doggie smell

doggie has an interesting smell

Does not match:

doggie smells

doggie is smelling

Example 2: dog.$

Matches:

sit, dog.

good dog!

Does not match:

sit, doggie

dogs.

In the example below, the hat and dollar sign operators are used together to

create a pattern that matches the entire "doggie smell" string from beginning

to end.

Example 3: ^doggie smell$

Matches:

doggie smell

Does not match:

big doggie smell

doggie has an interesting smell

doggie smells

The [] bracket expression

You use square brackets in regular expressions to match and include characters.

You can do so by listing out specific characters or using an alphanumeric range.

You can also use the square brackets in conjunction with a hat operator to

exclude characters.

Take the following patterns that include characters in the strings below:

Example 1: [aei]n

Matches:

ban

hen

Does not match:

undo

on

Example 2: robot [0-9]

Matches:

robot 7

brobot 180

Does not match:

robots 7

robot seven

Example 3: \.[dw]

Matches:

.whale

.dog

Does not match:

.cat

whale

The - inside brackets

You use the dash character to create character ranges

within square brackets.

Multiple ranges can be set in the same square brackets. For example, the

expression [A-Za-z0-9_] is often used to match all alphanumeric characters

in the English language.

Take the following expressions and strings below:

Example 1: [0-5] cats

Matches:

3 cats

33 cats

Does not match:

336 cats

3cats

Example 2: [A-D][l-p][o-s]

Matches:

Apple

Dose

Does not match:

apple

bone

Example 3: [a-z][0-9][A-Z]

Matches:

h4T

bl7XYZ

Does not match:

h44T

XYZ7bl

The ^ inside brackets

When using ^ inside of square brackets, you are denoting that you want to

exclude characters. In order to exclude characters,

you need to wrap the

operator and the characters you want to exclude within square brackets.

Example 1: [^b]

Matches:

hog

dog

Does not match:

bog

blog

Example 2: [^bc]at

Matches:

chat

rat

Does not match:

hat

cat

Example 3: [^bc]o[^g]

Matches:

hot

pot

Does not match:

cog

blog

RegexOne Practice

Just like with Flexbox Froggy and CSS Grid Garden, there are Web sites on the

Internet that really stand out as excellent resources from which to learn.

RegexOne is one of those resources.

It is a set of simple interactive exercises to help you practice your new-found

knowledge of regular expressions. Do all of the 15 exercises and eight problems.

HTTP Full-Stack Project

In this project, you are going to use Node.js to build a data-driven Web site.

This project already includes the Sequelize models and migrations for you. You

will create a Node.js HTTP server and use it to handle incoming requests from a

browser. Then, you will generate HTML to respond to the request.

Today's project does not address the aesthetics of the visual appearance of the

Web pages. You will have an opportunity later this week to do that. Today is

about functionality.

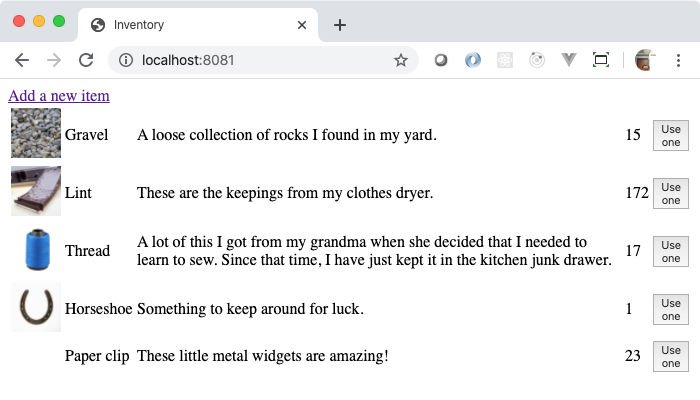

Project overview

You will build a simple inventory tracking system for managing the amount of

stuff that you have. The Sequelize data model is already created for you because

you now know how to do that pretty well. You'll get to flex those muscles later

this week, too.

You will build the server that accepts incoming HTTP requests using only

functionality built into Node.js. You will process the incoming request,

determine what needs to be done, and generate HTML to send back to the client.

This project shows you the underpinnings of how Node.js-based Web applications

work. Then, when you use a framework like Express.js or Koa.js, you will know

what they're doing.

The data model

To focus on the server portion of this, the data model is very simple. It

consists of one entity, the Item. The Item has the following properties.

| Property name | Data type | Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| name | string | not null, unique |

| description | text | not null |

| imageName | string | |

| amount | integer | not null, default 0 |

The functionality

You will create two HTML pages, one static and one dynamic. The static HTML page

will consist of a form that allows you to add new items that you want to track.

The dynamic HTML page will list the each item and its details and give you a

way to reduce the amount on hand.

Get started

-

Clone the starter repository from

https://github.com/appacademy-starters/node-web-app-starter. But, this time,

use an extended version of the Gitclonecommand to put it in a specific

directory. You will use the same starter project in the next project, too.git clone https://github.com/appacademy-starters/node-web-app-starter native-node-appInstead of creating a directory named after the repository,

"node-web-app-starter", this wil create a directory named "native-node-app"

and put the cloned repository into there. -

Change the working directory into "native-node-app"

-

Install the npm dependencies

-

Create a database user named "native_node_app" with the password

"oMbE4FNk3db2LwFT" and the CREATEDB privilege which will look likeCREATE USER ... WITH CREATEDB PASSWORD ...

You add the CREATEDB in there so you can do the next step and not be bothered

with creating the database yourself -

Run the Sequelize CLI with the

db:createcommand to create the database -

Run the Sequelize CLI to migrate the database

-

Run the Sequelize CLI to seed the database

Phase 1: Installing one tool

You will use a development tool to restart the server each time you make a

change to a JavaScript file. This prevents you from having to hit CTRL+C each

time you want to stop and start your server.

The tool is named nodemon and is the standard for this type of server

restarting. It is a development tool, so you will install it as a special kind

of dependency, a development dependency. You can do that with

npm install nodemon --save-dev

When you deploy your application to production, npm will ignore the development

dependencies because they're not needed when you run your application for other

people to use. Hopefully by that point, your Web application doesn't restart!

Phase 2: Getting the server started

Open the package.json file. It specifies that the "main" file for this

project is server/index.js. Create a server directory and an

index.js file in there.

Now, in package.json, find the "scripts" section. Add a new entry in there

named "dev" with the value "nodemon server/index.js". It should look like this.

"scripts": { "dev": "nodemon server/index.js", "test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1" },

That sets up a way to conveniently run the "nodemon" command by typing the

command npm run dev. You can run that right now. Because you have an empty

server/index.js file, it should report something like this:

[nodemon] starting `node server/index.js server/index.js`

[nodemon] clean exit - waiting for changes before restart

So, it's just waiting for you to add some code!

To get an HTTP server up and running, you will add code to do the following in

the server/index.js file.

- Import the built-in "http" module

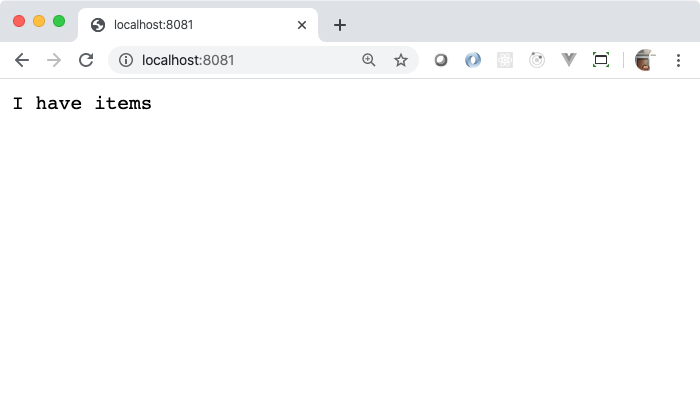

- Create a server using the "http" module that returns "I have items" to every

request - Tell that server to start listening on port 8081

- Print a message when the server is ready to accept incoming messages

Please look at the sample on the About Node.js® page. It has all of

the code

that you need to get the above done. You'll want to change the port number from

what it uses to 8081. You'll also want to change the text it sends to the

browser from what it reads to "I have items".

See if you can figure that out on your own. You'll know you're done when you

open up your browser to http://localhost:8081/ (or refresh it because

it's

already there) and see the following.

Phase 3: Understand the code

Hopefully, your code looks similar to the following code.

const http = require('http'); const hostname = '127.0.0.1'; const port = 8081; const server = http.createServer((req, res) => { res.statusCode = 200; res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/plain'); res.end('I have items'); }); server.listen(port, hostname, () => { console.log(`Server running at http://${hostname}:${port}/`); });

Just a reminder: the first three variable declarations and the last call to

listen are boilerplate code. Every time you write a Node.js server, you would

write the same code over and over. The real meat of the application is in the

callback function that you pass to createServer.

(req, res) => { // The code here is what matters. This is the stuff // that handles requests from the browser and sends // content back to it. }

The first parameter is the "request" object and is of type

http.IncomingMessage (link). The second parameter is

the "response" object and is of type http.ServerResponse (link).

In the code that you wrote, you set the status code of the response to 200 which

means "OK", if you recall. Then, you set the content type of the content of the

response to "text/plain" which means the browser should just show the content

as plain text. Finally, you use the end method to send some content and end

the response.

That last part is very important. If you don't end the response, the browser

will just hang, waiting, expecting more from your server.

In this project, you will use more methods and properties of the

IncomingMessage and ServerResponse objects to get your application working.

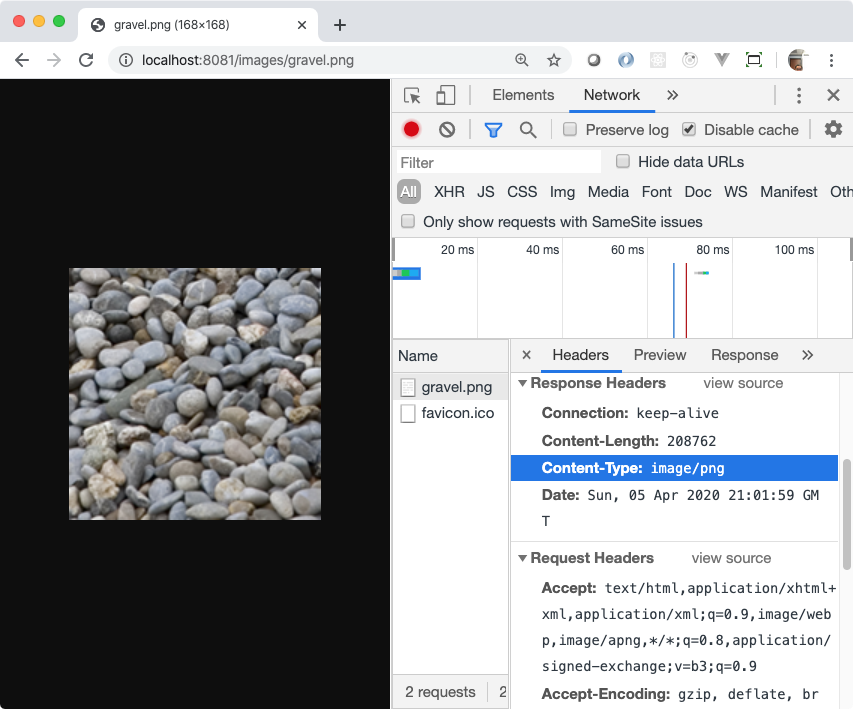

Phase 4: Showing images

In the assets/images directory of this project are four images that your

server should be able to show. (And more, if you add more.)

A normal thing to do is to translate a URL to a path relative to your

application's root directory. For example, say you typed the following URL into

your browser.

http://localhost:8081/images/thread.jpeg

It would make sense to have the server send back the content of

assets/images/thread.jpeg so the browser can show it. That's what you will

do in this step, but for any of the images.

You'll need a way to read the contents of each file. The modern way to do this

is to use the Promises-based portion of the file system library. At the top of

your index.js, import the readFile function from the "promises" property

of "fs" library.

const { readFile } = require('fs').promises;

You will use the await keyword with that function, so you need to change the

signature of the callback method that you pass to the createServer method.

Note the addition of the async keyword before the parameter list.

const server = http.createServer(async (req, res) => {

Again, you will map requests for images to the corresponding file in the

images directory. It looks like this.

http://localhost:8081/images/filename.ext

\__________________/

|

+------------+

_______|_________

/ \

./assets/images/filename.ext

If the image exists, you'll send the contents of the image to the browser. If it

does not, then you will tell the browser that it does not exist by sending a 404

NOT FOUND status code.

Phase 4a: The happy path

To determine if the path is one that you want, at the top of your async

callback, put an if statement that tests if the req.url property (which is a

string) starts with "/images/". Replace the comment below to do that.

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => { if (/* req.url start with "/images" */) { } res.statusCode = 200; res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/plain'); res.end('I have items'); });

If the test passes, that means that req.url will contain a string like

"/images/thread.jpeg". That means that you will want to load the file from

"./assets/images/thread.jpeg" which is the concatenation of the string

"./assets" and the value of req.url. This code goes inside the if block.

const imageFilePath = './assets' + req.url; const imageFileContents = await readFile(imageFilePath);

Notice that you did not specify 'utf-8' as part of the readFile call.

That's because the content of an image file is not UTF-8 encoded text.

Instead, it's binary. This way without the encoding just returns the raw data

that is then sent to the browser.

After that, you need to should set the status code of the response to 200 to

indicate everything is OK. Then, you need to set the content type which takes a

little bit of figuring, so you can delay that for just a moment. Assume that the

browser has requested an image in the JPEG format. Finally, you end the response

by sending the data of the file that you read.

Add this code inside the if block after reading the file's contents.

res.statusCode = 200; res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'image/jpeg'); res.end(imageFileContents); return;

The return at the end prevents any other code after it to run, that code at

the bottom that sends back plain text.

You should now be able to see any of the following in your browser!

- http://localhost:8081/images/thread.jpeg

- http://localhost:8081/images/horseshoe.jpeg

- http://localhost:8081/images/lint.jpeg

Most likely, you can also see the following image, too.

That's because browsers are really for giving. Even though you tell the browser

that you are sending JPEG data with the content type "image/jpeg", the browser

inspects the data and figures out it's an image in the PNG format. But, you

should not rely on the forgiveness of the browser. Instead, you should determine

the type of image format the file contains from the file extension, either

".jpeg" or ".png". Then, you send back "image/jpeg" or "image/png" based on the

file extension.

You can use the built-in "path" library to determine the file extension. Then,

you can use that information to send back the correct image format type in the

setHeader method.

At the top of the index.js file, import the "path" library.

const path = require('path');

Here's a link to the "path" library: https://nodejs.org/api/path.html. Find the

method that will extract the file extension from a path. Then, use that in

your code to send back the correct image type.

const fileExtension = /* Use the path library to get the file extension */; const imageType = 'image/' + fileExtension.substring(1); res.statusCode = 200; res.setHeader('Content-Type', imageType); // Use the image type

Make sure you still see "I have items" when you go to http://localhost:8081.

Phase 4b: No image found

Try accessing this URL: images/unknown.png. You will see

an error message in your console about an unhandled promise rejection not being

able to open './assets/images/unknown.png'. Worse yet, the browser is just

hanging. That's because this line of code:

const imageFileContents = await readFile(imageFilePath);

threw an error, it wasn't handled, and the end method never gets called on the

response object. That means the browser just waits and waits and waits.

If you get a request for an image that does not exist, you can just catch this

error and send back a 404 and no content. Replace that single line of code

above with this block of code.

Wrap that line of code above in a try/catch block. In the catch block,

set the status code of the response to 404. Then, just call the end method

of the response with no parameters. The last statement of the catch block

should be a return; statement to prevent other code from running after you

handle this error.

You'll have to fix the declaration of the imageFileContents variable so that

it works.

Refresh the browser. You should now get a 404 page when you try to access an

image that does not exist. You should see the images that do exist when you go

to their corresponding URLs.

Make sure you still see "I have items" when you go to http://localhost:8081.

Phase 5: Showing a static HTML page

Here's some HTML that shows a form that you will use to add new items to the

database. You will serve this statically. That means you won't change any of

its contents. Instead, you'll just read the file from disk and send it to the

browser.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <title>Add an item</title> </head> <body> <header> <a href="/">Back to the main page</a> </header> <main> <form method="post" action="/items"> <div> <label for="name">Name</label> <input type="text" name="name" id="name" required> </div> <div> <label for="description">Description</label> <textarea name="description" id="description" required></textarea> </div> <div> <label for="amount">Starting amount</label> <input type="number" name="amount" id="amount" required> </div> <div> <button type="submit">Create a new item</button> </div> </form> </main> </body> </html>

You'll learn a lot more about forms, this week. There are three things to note

about this form.

- The "method" attribute of the

formelement is "post" which means the value

ofreq.methodin our request handler will be "POST". (It is always

uppercase when read from thereq.methodproperty.) - The "action" attribute of the

formelement is "/items". That will be the

value ofreq.urlthat you will need to check when you want to handle the

form submission. - The "name" attribute of the

inputandtextarea(and all form elements) are

the keys that we will use to get the values that a person supplies by typing

into the form.

Create a views directory in the root of your project. Save the HTML into a

file there named add-item.html.

To serve this HTML, create a new if block that checks to see if the value of

the req.url property is equal to "/items/new". If it is, then do what you did

with the images. The path to the HTML file should be "./views/add-item.html".

Read the file's contents. Set the status code to 200. Set the content type to

"text/html". Send the content of the file to the browser and end the response.

Use a return; statement to make sure no other code runs.

When you get that working, you should be able to navigate to

http://localhost:8081/items/new and see this.

Phase 6: First step in dynamic content

Navigate your browser back to http://localhost:8081 where you see "I

have

items". (If that's not working, figure out how it broke and fix it.) Now, you

will query the database for the number of items in it and report it. Instead of

seeing "I have items", it should report something like "I have 4 items".

This is primarily Sequelize code. At the top of index.js, import the Item

model.

const { Item } = require('../models');

Down at the bottom of your callback after your if blocks and before the line

that reads res.statusCode = 200;, use the findAll method of the Item model

to get all of the items in the database. That should return an array of the

objects. Use the length of that array to show the current number of items in the

database by changing res.end('I have items'); to include the number of items.

It may surprise you to learn that this is really what most Web applications do.

Read some data from a database. Use that data to generate some content. Send

the content to the browser. That's the simple recipe.

Do something real quick before the next phase. Instead of serving plain text,

here, change that content type to serve HTML. Then, in whatever string you're

passing to the res.end method, add this HTML snippet at the beginning of it so

you can easily get to the "add a new item" form.

<div><a href="/items/new">Add a new item</a></div>

Test the link by clicking on it. It should take you to the form.

Phase 7: Handling the adding of an item

Now's the time to handle the adding of an item from that form! Click the link

to get to the add the form or navigate to http://localhost:8081/items/new in

your browser. If you fill out the form and click the button, it just takes you

back to the main page and doesn't do anything. It's time to change that.

Add a new if block that checks that both of these conditions are true:

- The value of

req.urlis equal to "/items" - The value of

req.methodis equal to "POST"

Inside that if block is where you will handle the data that someone sends to

the server through the form. You'll use it to create a new Item and save it to

the database. Then, you'll redirect back to the main page.

Phase 7a: Getting the submitted data

Open up your developer tools. On the Network tab, click the "Preserve log"

checkbox above the timeline. Then, fill out the form and click the "Create a new

item" button. That will make the request. Select the "items" entry in the list

of network requests below the timeline. You should see a section entitled

Form Data. Click the "view source" link.

What you see is likely like this, but with whatever values you put in the

fields.

name=Shoe&description=I+have+one+shoe+that+I+cant+seem+to+find+its+pair.+So%2C+I+guess+I+have+one+of+those.&amount=1

That's the content that is sent with the HTTP request to your server. The full

HTTP request looks something like

POST /items HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:8081

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 116

... more headers ...

name=Shoe&description=I+have+one+shoe+that+I+cant+seem+to+find+its+pair.+So%2C+I+guess+I+have+one+of+those.&amount=1

That's the "URL encoded" format that you read about in the Five Parts Of A URL

reading. You'll parse that in the next step. What you have to do, now, is get it

from the IncomingMessage object. That object is a readable stream, so you will

read the bytes from the stream and turn them into a string to use in the next

step.

When your callback is invoked by the server object, it has only read the

headers portion of the HTTP request. The body of the HTTP request (if there is

one) could still be traveling over the airwaves and wires from your computer to

the server. This way, your Web application can look at the values in the headers

and determine whether or not it wants to even respond. Maybe the content length

is 400Gb. You don't want your server spending however long it takes to read all

of that data, so you can just end it.

To do this easily, you will use a variety of the for loop that works with

asynchronous iterable values as well as normal one. It is the for

await...of

loop. Like the for of loop, it loops over values rather than indexes. But, the

value after the of can return Promises which the for loop will wait on for

them to resolve before invoking the block of code.

That's a lot of words. Here's what it looks like. Put this in your if block

that handles "POST /items".

let body = ''; for await (let chunk of req) { body += chunk; } // body now contains all of the data // from the request

This works because req is an IncomingMessage message object which inherits

from ReadableStream which implements the asynchronous iterator

property.

Phase 7b: Parsing the submitted data

Now that you have all of the data in the body variable, it's time to split it

up into the data that you want. From the form, it will look like this as a raw

string:

name=value1&description=value2&amount=value3

Use string manipulation to break that into its separate pieces so that you can

access each of key value pairs.

- Split the string on ampersands, first.

- Split each value from the previous step on equal signs.

To handle the encoded values on the right side of the equal sign, it is a

two-step process:

- Replace each of the "+" characters with a space. You have to use a global

regular expression to do this with thereplacemethod because JavaScript

will only replace the first occurrence in the string without a global

regular expression. If the value is in a variable nameds, you would call

s.replace(/\+/g, ' ')to replace all of the "+' characters in a string with

spaces. - After replacing the plusses, take the value and pass it to the

decodeURIComponentfunction which will go about translating the percent-sign

encoded values into single characters.

Phase 7c: Create an Item

You should have the data broken into pieces that you can now access. Use your

Item model to build and save (or create) a new item.

Phase 7d: Redirect the browser

Redirecting the browser to go to another URL is a two-step process, too. You

send back status code 302. You also set the header "Location" to the URL that

you want it to navigate to. For this project, set the "Location" to "/". Then

end the response.

Make sure that you use a return statement or something to prevent the default

code at the bottom of your request handler from running.

Phase 8: Generate dynamic content

At the bottom of your handler, you've already queried the items in your Item

objects from the database. Now, it is time to show the items rather than just

displaying how many are in the database.

You can use the write method of the ServerResponse object in the res

to

write your HTML to the browser as you're generating it. Your code may look

something like this.

const items = await Item.findAll(); res.statusCode = 200; res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/html'); res.end(` <div><a href="/items/new">Add a new item</a></div> I have ${items.length} items `);

Take a look at this code which just expands on the previous block. It writes the

proper beginning of an HTML document, then writes the dynamic content, then ends

it with the proper end of an HTML document.

const items = await Item.findAll(); res.statusCode = 200; res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/html'); res.write(` <!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <title>Inventory</title> </head> <body> <header> <div><a href="/items/new">Add a new item</a></div> </header> <main>`); res.write(`I have ${items.length} items`); res.end(` </main> </body> </html>`);

In the place where there's only the one line of dynamic content, change it to

have something else, something that shows the name of the item, the amount of

them you have, and the associated image, if imageName is not null or

undefined.

The following screenshot shows where an open table tag has been added to the

end of the string for the first write, a close table tag has been added to the

beginning of the string of the res.end call, and looping is used to create a

new table row (tr) with table data (td) for each of the properties of the

Item.

It looks, in part, like this.

for (let item of items) { res.write(` <tr></td> `); // Only write an IMG tag if there is a value // in imageName res.write(` </td> <!-- Write more TDs here with the details of the item --> <td>`); if (item.amount > 0) { res.write(` <form method="post" action="/items/${item.id}/used"> <button type="submit">Use one</button> </form> `); } res.write(`</td> </tr>`); }

As seen above, for each item, you should also create a form that has the

following content for items with an amount greater than 0.

<form method="post" action="/items/«item id»/used"> <button type="submit">Use one</button> </form>

That's the last handler that you'll write to complete the project!

Phase 9

When there is a POST request to the path "/items/«item id»/used", you want to

reduce the amount by 1 of the item specified by the «item id» in the path. Write

another if block that handles that HTTP request. Parse the id from the path.

Use that id to get the Item from the database. Reduce the amount by 1. Save the

Item back to the database. Redirect back to "/".

Complete!

That was quite a ride! You created a full-stack Web application! You pulled data

from a database to generate HTML. You sent the HTML to the browser. You handled

requests, both GET and POST, from the browser to interact with and modify the

data in the database. This is literally what Web developers do every single day.

Except with better tools. Tools like you learn about tomorrow.

<=(Express)==>

- <=(Node HTTP Servers)=>

- Regular Expressions Learning Objectives

- HTTP Full-Stack Learning Objectives

- The Uniform Resource Locator (URL)

- Regular Expressions Cheat Sheet

- RegexOne Practice

- HTTP

Full-Stack Project

- Project overview

- Get started

- Phase 1: Installing one tool

- Phase 2: Getting the server started

- Phase 3: Understand the code

- Phase 4: Showing images

- Phase 4b: No image found

- Phase 5: Showing a static HTML page

- Phase 6: First step in dynamic content

- Phase 7: Handling the adding of an item

- Phase 8: Generate dynamic content

- Phase 9

- Complete!

- <=(Express)==>

- Express Learning Objectives

- Pug Template Learning Objectives

- Moving Into the Express Lane

- Templating - Meet Pug!

- Digging Into the Pug Template Syntax

- Exploring Route Paths

- Express Routers

- Routing Roundup Project

- <=(Form Handeling)==>

- HTML Forms Learning Objectives

- HTML Forms: An Introduction

- HTML Forms in Express

- Data Validation

- Express Middleware

- Protecting forms from CSRF

- Formative Forms Project

- <=(Express)==>

Express Learning Objectives

Express is the de facto standard for building HTTP applications with Node.js.

When you complete this lesson, you should be able to

- Send plain text responses for any HTTP request

- Use pattern matching to match HTTP request paths to route handlers

- Use the Pug template engine to generate HTML from Pug templates to send to the

browser - Pass data to Pug templates to generate dynamic content

- Use the

Routerclass to modularize the definition of routes

Pug Template Learning Objectives

Using Pug.js helps reduce the overall creation and maintenance of source code

for HTML generation. It is one of many template engines supported by Express.js

and remains one of the most popular. At the end of this lesson, you will be able

to effectively use Pug.js to

- Declare HTML tags and their associated ids, classes, attributes, and content

- Use conditional statements to determine whether or not to render a block

- Use interpolation to mix static text and dynamic values in content and

attributes - Use iteration to generate multiple blocks of HTML based on data provided to

the template

Moving Into the Express Lane

In an earlier lesson, you created a simple HTTP server using JavaScript and

Node.js. That HTTP server, or web application, returned a simple response based

upon the incoming request's URL (and HTTP method in one case). For example, a

request to the URL http://localhost:300/OK returned a 200 OK HTTP response

status code.

Overall, this was easy to do using Node's native APIs, though the requirements

were relatively straightforward. Using Node to create a web application with

features commonly found in websites unfortunately requires a fair amount of

boilerplate code (i.e. verbose, repetitive code). This can slow down and

distract developers from working on more important tasks.

Enter Express, a popular Node.js framework for building web applications.

Express aims to make common web development tasks easier to implement by

reducing the amount of boilerplate code you need to write. This allows you to

focus on the things that makes your web application special. At the same time,

Express is, in its own words, unopinionated and minimalistic, giving you the

flexibility to decide what's best for your situation.

As an introduction to Express, let's create a simple web application. Your

application will return a plain text response containing "Hello from Express!"

for any request to http://localhost:8081/.

When you finish this article, you should be able to:

- Use the

express()function to create an Express application; - Recall that routing is determining how an application responds to a client

request to a specific URI (or path) and HTTP method combination; - Use the Application

get()method to define a route that handlesGET

requests; - Use the Response object

res.send()method to send a plain text response to a

client; and - Use the

app.listen()method to start a server listening for HTTP connections

on a specific port.

Installing Express

Before you can use Express to create a web application, you need to install it

using npm. Open a terminal or command prompt window, browse to your project's

folder, and initialize npm by running the following command:

npm init -y

You'll now have package.json and package-lock.json files in the root of your

project. The package.json file keeps track of your application's

dependencies—npm packages that your application needs to successfully start and

run.

Run the following command to install Express 4.0:

npm install express@^4.0.0

The package.json file will now list Express as a dependency:

{ "name": "my-project-folder-name", "version": "1.0.0", "description": "", "main": "index.js", "scripts": { "test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1" }, "keywords": [], "author": "", "license": "ISC", "dependencies": { "express": "^4.17.1" } }

At the time of this writing, the latest version of Express 4.0 is

4.17.1.

While newer minor or patch versions of Express 4.0 should work fine, newer

major versions (5.0+) might not work as expected. The caret character (^)

the precedes the version number in thepackage.jsonfile (^4.17.1)

instructs npm to allow versions greater than4.17.1and less than5.0.0.

Git and the node_modules folder

In an earlier lesson, you learned that when using npm install to install an

npm package locally into your project, npm downloads and installs the specified

package to the node_modules folder. Over time, as you install dependencies,

the node_modules folder tends to grow to be very large, containing many

folders and files.

If you're using Git for source control, it's important to add a .gitignore

file to the root of your project and add the entry node_modules/ so that the

node_modules folder won't be tracked by Git.

As alternative to creating your own

.gitignorefile, you can use GitHub's

comprehensive.gitignorefile for Node.js projects.

Creating an Express application

Now you're ready to create your Express application!

Add a file named app.js to your project folder and open it in your code

editor. Use the require directive to import the express module and assign it

to a variable named express. The express variable references a function

(exported by the express module) that you can call to create an Express

application. Assign the return value from the express function call to a

variable named app:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express();

The app variable holds a reference to an Express Application (app) object.

You'll call methods on the app object as you build out your web application.

Handling requests

Next, you need to configure the routing for your application.

The process of configuring routing is determining how an application should

respond to a client request to an endpoint—a specific URI (or path) and HTTP

method combination. For example, when a client makes a GET request to your

application by browsing to the URL http://localhost:8081/, it should return

the plain text response "Hello from Express!".

Do you remember the parts of a URL? In the URL

http://localhost:8081/,

the protocol ishttp, the domain islocalhost, the port is8081(we'll

see in a bit how to configure the port for your application), and the path is

/.

The Express Application (app) object contains a collection of methods for

defining an application's routes:

get()- to handleGETrequestspost()- to handlePOSTrequestsput()- to handlePUTrequestsdelete()- to handleDELETErequests

GET and POST are two of the most commonly used HTTP methods, followed by

PUT and DELETE.

See the Express documentation for a complete list of the available routing

methods.

To define a route to handle GET requests, call the app.get() method passing

in the route path and a route handler function:

app.get('/', (req, res) => { // TODO Send a response back to the client. });

Express provides a lot of flexibility with the format of the route path. A route

path can be a string, string pattern, regular expression, or an array containing

any combination of those. For now, you'll just use a string, but in later

articles you'll see how to use the other options.

The route handler function is called by Express whenever an incoming request

matches the route. The function defines two parameters, req and res, giving

you access respectively to the Request and Response objects. The Request (req)

object is used to get information about the client request that's currently

being processed. The Response (res) object is used to prepare a response to

return to the client.

To send a plain text response to the client, call the res.send() method

passing in the desired content:

app.get('/', (req, res) => { res.send('Hello from Express!'); });

Here's the code for your application so far:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express(); // Define routes. app.get('/', (req, res) => { res.send('Hello from Express!'); });

Listening for HTTP connections

Great job so far! Now you need to start the server listening for HTTP

connections from clients. To do that, call the app.listen() method passing in

the desired port to use and an optional callback function:

const port = 8081; app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}...`));

The callback function will be called when the server has started listening for

connections. Logging a message to the console gives you an easy way to see when

the server is ready for testing.

Here's the complete code for your application:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express(); // Define routes. app.get('/', (req, res) => { res.send('Hello from Express!'); }); // Define a port and start listening for connections. const port = 8081; app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}...`));

Testing your application

To test your application, open a terminal or command prompt window, browse to

your project's folder, and run the following command:

node app.js

If your application starts successfully, you'll see the text "Listening on port

8081…" displayed in the terminal or command prompt window. Next, open a web

browser and browse to the address http://localhost:8081/. You should see the

text "Hello from Express!" displayed in the browser.

If you see the expected text, congrats! If you don't, double check the

following:

- Make sure that you started your application by running the command

node app.js. - Double check that the URL you entered into your browser's address bar is

http://localhost:8081/. - Check the terminal or command prompt window to see if an error is occurring.

What you learned

In this article, you learned

- how to use the

express()function to create an Express application; - that routing is determining how an application responds to a client request to

a specific URI (or path) and HTTP method combination; - how to use the Application

get()method to define a route that handlesGET

requests; - how to use the Response object

res.send()method to send a plain text

response to a client; and - how to use the

app.listen()method to start a server listening for HTTP

connections on a specific port.

See also…

As you learn about Express, you'll find it helpful to explore Express' official

documentation at expressjs.com.

Templating - Meet Pug!

In a previous article, you learned how to use the Response object's res.send()

method to send a plain text response to the client. Sending plain text is, well,

plain! A much more common content format when sending a response to browser

clients is HTML.

You could use the res.send() method to send a string of HTML content to

the client:

app.get('/', (req, res) => { res.send(` <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head><title>Welcome</head></title> <body> <h1>Hello from Express!</h1> </body> </html> `); });

While it works, using this technique is tedious and prone to errors. Can you

spot the error in the above HTML (hint: look at the nesting of the HTML

elements)?

Luckily, there's a better way. Developers have used templates (files that

contain markup and code) to render HTML content for many years (that's

practically centuries in internet time!) Express integrates with many popular

templating engines (libraries that provide support for writing templates). In

this article you'll learn how to use the popular Pug templating engine to

render HTML content.

When you finish this article, you should be able to:

- Create a Pug template that contains one or more variables;

- Use the

app.set()method and theview engineapplication setting property

to configure Express to use the Pug template engine; and - Use the Response object

res.render()method to render a Pug template to send

an HTML response to a client.

What is a template?

A template allows developers to easily combine static and dynamic content.

Templates are typically written using a special, proprietary syntax to make it

as easy as possible for developers to create content. Here's an example of a

simple Pug template:

html head title Welcome body h1 Welcome #{username}!

Notice the lack of angle brackets (i.e. < and >) in this example on the

html, head, title, body, and h1 elements.

You also don't have to close elements. Pug will take care of that for you. It

uses indents to determine which elements are children of other elements. In the

above example, head is a child of html because head is indented more

than

html. When Pug turns that into HTML, it will place the <head>...</head>

element inside the <html>...</html> element. Look at all the typing that Pug

has saved you!

Element content is provided just to the right of the element name. The content

for the title element is "Welcome" and the content for the h1 element is

"Welcome #{username}!".

At runtime, the templating engine combines data (often retrieved from a

database) with a template to render the content for the response to return to

the client. In the above template, Pug will replace the text #{username} with

the username variable value that you give it when you tell express to render

that template. Assuming that the username variable is set to the value

mycoolusername, Pug would render the following HTML:

<html><head><title>Welcome</title></head><body><h1>Welcome mycoolusername!</h1></body></html>

Pug, by default, removes indentation and all whitespace between elements.

In some rare cases you might need to manually control how whitespace

is handled. For information on how to do this, see the official Pug

documentation.

Rendering a simple template

Before we further explore Pug's template syntax, let's see how to use Express to

render a simple template to send a response to a client.

Setting up the project

Create a folder for your project, open a terminal or command prompt window,

browse to your project's folder, and initialize npm. (You use the -y flag so

that you don't have to answer those annoying questions. npm will just use

default values for everything.)

npm init -y

Then install Express using npm.

npm install express

Now you're ready to create the application. Add a file named app.js to your

project folder. Import the express module and assign it to a variable named

express, then call the express function and assign the return value to a

variable named app:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express();

In the previous article, you used the app.get() method to define a route for

handling GET requests. As an alternative to the app.get() method, Express

provides a method named all() that can be used to define a route that handles

any HTTP method.

Call the app.all() method, passing in an asterisk (*) for the route path and

a route handler function that calls the res.send() method to send a plain text

response to the client:

// Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { res.send('Hello from the Pug template example app!'); });

Remember that the route handler function is called by Express whenever an

incoming request matches the route. The function defines two parameters, req

and res, giving you access respectively to the Request and Response objects.

The asterisk (*) in the route path is a wildcard character that will match any

number of characters in the incoming request's URL path (e.g. /, /about,

/about/foo, and so on). Combining this route path with the get.all() method

defines a route that will match any incoming request, regardless of its path or

HTTP method.

This approach is unorthodox and not commonly seen in real world applications.

Generally speaking, you should prefer to use theappmethods that map to

individual HTTP methods. We're using theapp.all()in this article to

demonstrate the flexibility that Express provides when defining routes.

When a route can match any incoming request it can be helpful to know the

current request's method and path. The Request object passed into the route

handler function via the req parameter provides information about the incoming

request. You can log two Request object properties in particular, req.method

and req.path, to the console to see the current request's method and path:

// Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { console.log(`Request method: ${req.method}`); console.log(`Request path: ${req.path}`); res.send('Hello from the Pug template example app!'); });

The Express Request and Response objects provide a number of helpful

properties and methods for working with HTTP requests and responses. To learn

more, see the official Express docs for the Request and

Response objects.

Now start the server listening for HTTP connections by calling the

app.listen() method:

// Define a port and start listening for connections. const port = 8081; app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}...`));

Here's what the code for your application should look like at this point:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express(); // Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { console.log(`Request method: ${req.method}`); console.log(`Request path: ${req.path}`); res.send('Hello from the Pug template example app!'); }); // Define a port and start listening for connections. const port = 8081; app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}...`));

To test your application, open a terminal, browse to your project's folder, and

run the command:

node app.js

The text "Listening on port 8081…" should display in the terminal or command

prompt window. Open a web browser and browse to the address

http://localhost:8081/ to confirm that the application sends a response

containing the plain text "Hello from the Pug template example app!".

Creating a template

Templates are stored in the views folder by default. To create a template, add

a folder named views to your project, then add a file named layout.pug

containing the following code:

html head title= title body h1= heading

The assignment operator (=) following the title and h1 element names

instructs Pug to set the content for those elements respectively to the title

and heading variables.

You'll learn more about how to render data in a Pug template in a later

article.

Configuring Express to use a template engine

Before you can use the Pug template engine in an Express application, you need

to install it:

npm install pug@^2.0.0

To configure Express to use Pug as its default template engine, call the

app.set() method and set the view engine application setting property to the

value pug:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express(); // Set the pug view engine. app.set('view engine', 'pug');

The

view engineproperty is just one of the available application settings.

For a list of available settings see the Express documentation.

Setting the view engine application setting property isn't required, but it

has the following benefits:

- It makes it clearer to code reviewers that your application is using the Pug

template engine; and - You don't have to supply the file extension of the template when rendering a

template (we'll see how this works next).

Rendering a template

Now you're ready to update your application to use your template. Update your

route handler function to call the Response object's res.render() method,

passing in the name of the template:

// Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { console.log(`Request method: ${req.method}`); console.log(`Request path: ${req.path}`); res.render('layout'); });

At this point, if run and test your application, you won't see any content

displayed in the browser.

If you left your application running in the terminal or command prompt window,

you'll need to stop and restart it so that Node picks up your latest code

changes. To do that, pressCTRL+Cto stop the application and runnode app.jsto restart the application.

If you view the source for the page in the browser, you'll see the following

HTML:

<html><head><title></title></head><body><h1></h1></body></html>

Notice that the title and h1 elements don't have any content. The template

expects data for the title and heading variables, but you're currently not

passing any data. To fix that, pass an object literal containing title and

heading properties as a second argument to the res.render() method call:

// Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { console.log(`Request method: ${req.method}`); console.log(`Request path: ${req.path}`); const pageData = { title: 'Welcome', heading: 'Home' }; res.render('layout', pageData); });

Now if run and test your application, you should see the expected content

displayed in the browser.

Here's what the code for your application should look like after updating it to

render the Pug template:

app.js

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express(); // Set the pug view engine. app.set('view engine', 'pug'); // Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { console.log(`Request method: ${req.method}`); console.log(`Request path: ${req.path}`); const pageData = { title: 'Welcome', heading: 'Home' }; res.render('layout', pageData); }); // Define a port and start listening for connections. const port = 8081; app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}...`));

views/layout.pug

html head title= title body h1= heading

What you learned

In this article, you learned

- how to create a Pug template that contains one or more variables;

- how to use the

app.set()method and theview engineapplication setting

property to configure Express to use the Pug template engine; and - how to use the Response object

res.render()method to render a Pug template

to send an HTML response to a client.

Digging Into the Pug Template Syntax

Now that you've seen how to create and render a simple Pug template, let's

explore Pug's syntax in more depth. Learning Pug's syntax takes time and effort,

but the payoff is that writing and maintaining templates will generally take

less time overall.

When you finish this article, you should be able to use the Pug template syntax

to:

- Render elements;

- Set element attribute values;

- Set element class and ID attribute values;

- Set element content from a variable;

- Set an element attribute value from a variable;

- Inject a variable value into text using interpolation;

- Iterate the elements in an array to generate content; and

- Conditionally display content.

Setting up a sandbox application

Exercise your brain! Use the following application as a sandbox to test

and experiment with the Pug syntax as it's introduced in this article. Doing

this will help you to remember what you've learned.

Create a folder for your project, open a terminal or command prompt window,

browse to your project's folder, and initialize npm:

npm init -y

Then install Express 4.0 and Pug 2:

npm install express@^4.0.0 pug@^2.0.0

Add a folder named views to your project, then add a file named layout.pug

containing the following code:

html head title= title body h1= heading

Then add a file named app.js to your project folder containing the following

code:

const express = require('express'); // Create the Express app. const app = express(); // Set the pug view engine. app.set('view engine', 'pug'); // Define a route. app.all('*', (req, res) => { console.log(`Request method: ${req.method}`); console.log(`Request path: ${req.path}`); res.render('layout', { title: 'Pug Template Syntax Sandbox', heading: 'Welcome to the Sandbox!' }); }); // Define a port and start listening for connections. const port = 8081; app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}...`));

To test your application, open a terminal or command prompt window, browse to

your project's folder, and run the command:

node app.js

The text "Listening on port 8081…" should display in the terminal or command

prompt window. Open a web browser and browse to the address

http://localhost:8081/ to confirm that the application sends a response that

displays an HTML <h1> element containing the text "Welcome to the Sandbox!".

Rendering elements

Consider the following excerpt from a Pug template:

ul li Item A li Item B li Item C

This renders an HTML unordered list:

<ul> <li>Item A</li> <li>Item B</li> <li>Item C</li> </ul>

Text at the beginning of a line (with or without white space) represents an HTML

element. Any text included after the element name will be added as the element's

inner text. To add an element as a child element, simply indent the line for the

child element by one or more spaces (two spaces is a common convention).

Whether you decide to use two or four spaces for indenting elements, it's

important to keep your indentation consistent throughout the template. Not

doing so might result in Pug throwing an error at runtime.

Setting element attribute values

To set attribute values on an element, follow the element name with a pair of

parentheses containing one or more attribute name/value pairs:

a(href='/about' class='menu-button') About

Renders to:

<a href="/about" class="menu-button">About</a>

Setting class and id

attribute values

Element class and ID attributes are very common attributes to set, so Pug

provides a shortcut syntax for each. You can set an element's class attribute

using the syntax .classname and an element's id attribute using #idname:

div#container a.button Cancel

Renders to:

<div id="container"> <a class="button">Cancel</a> </div>

You can also combine a class name with an ID name or chain multiple class names:

div#container.main a.button.large Cancel

Renders to:

<div id="container" class="main"> <a class="button large">Cancel</a> </div>

This example can be further condensed. <div> elements are so common, Pug

allows you to remove the <div> element's name:

#container.main a.button.large Cancel

Rendering data

As you saw in an earlier article, you can provide data to a template by passing

an object to the res.render() method:

res.render('layout', { firstName: 'Grace', lastName: 'Hopper' });

Properties on the object passed as the second argument to the res.render()

method are defined within a template as local variables, which can be used to

set element content:

ul li= firstName li= lastName

Which would render to:

<ul> <li>Grace</li> <li>Hopper</li> </ul>

Variables can also be used to set element attribute values:

form div label First Name: input(type='text' name='firstName' value=firstName) div label Last Name: input(type='text' name='lastName' value=lastName)

Renders to:

<form> <div> <label>First Name:</label> <input type="text" name="firstName" value="Grace"/> </div> <div> <label>Last Name:</label> <input type="text" name="lastName" value="Hopper"/> </div> </form>

You can also use interpolation to inject a variable value into text:

p Welcome #{firstName} #{lastName}!

Renders to:

<p>Welcome Grace Hopper!</p>

Notice how Pug's interpolation syntax

#{expression}differs from

JavaScript's string template literal interpolation syntax${expression}. In

a Pug template, the text to the right of the element name is just plain text,

not JavaScript.

Iteration and conditionals

You can even use dynamic data to control the generation of HTML in your